Why does Maywood Park exist?

A neighborhood thought they could stand up to midcentury American highway expansion. They were wrong.

Why is Portland Like That? is a weekly Q&A column that answers your questions about the Rose City. If you want to ask a question, send me an email.

Sydney asks: What's the deal with Maywood Park? Why's that a thing?

Portland has a weird triangular hole in it. Maywood Park is a city-within-a-city that’s all of 0.17 square miles with fewer than a thousand people. It’s essentially a small neighborhood with its own city government.

Because Maywood Park is entirely surrounded by Portland, you might think that it seceded from the city. It appears that a small, wealthy enclave left Portland for some reason, and maintains some kind of pseudo-independence to this day. That’s not exactly what happened.

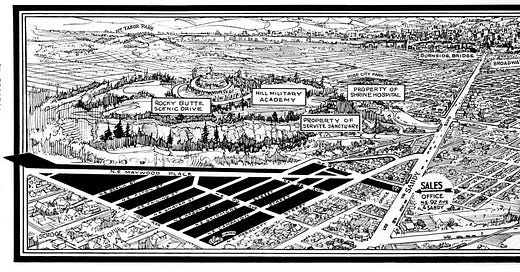

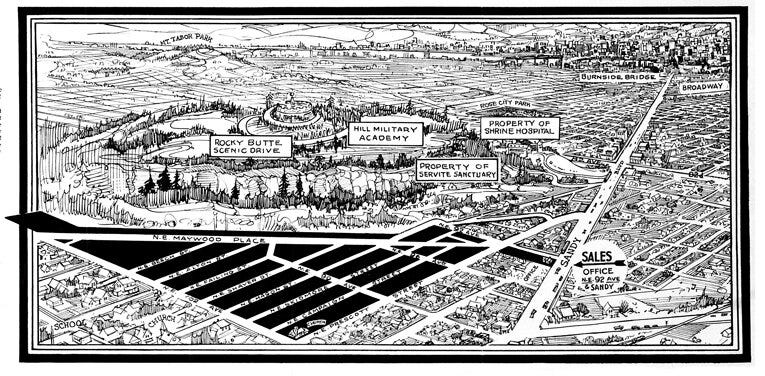

Maywood Park started as a nice-ish housing development on unincorporated land just east of Rocky Butte. It has easy access to the core of Portland via Sandy Boulevard, and had the same middle-class appeal of neighborhoods like Laurelhurst and Irvington. Apparently it’s called “Maywood” because the trees looked nice in May, a name that truly speaks the massive and inspiring creativity of midcentury real estate developers.

At least it did before I-205 went up.

Nowadays in the U.S. we’re used to highways cutting through urban areas (more on that below) but in the middle twentieth century there was still a significant amount of debate about where these car-filled monstrosities would live. Obviously they’d connect cities. But would they go through them? Or around them?

The residents of what would become Maywood Park thought that if they incorporated into their own city they could have some sway over the route of I-205. They didn’t think that transportation officials would actually route the highway through a real city, however small. Right? Surely destroying pleasant and expensive single-family homes in real, live city would be unthinkable, yes?

Interstate 205 goes right through Maywood Park, and highway construction did indeed destroy 82 homes. The tiny city was able to get some noise mitigation infrastructure put up, but the city lost its fight against the 205. Presumably, as each house was destroyed to make for a highway, Robert Moses cackled with delight as an every-expanding network of concrete encircled the North American continent.

Maywood Park is a thing because of NIMBYism, but it’s NIMBYism weaponized against a highway. My distaste for homeowners who oppose change is dwarfed by my distaste for freeways, the gigantic avenues of alienation that cut through American cities. When it comes to opposing highway expansion, I have to give it to the busybodies who try to stop a thing from happening.

Portland eventually grew around Maywood Park, gradually taking in unincorporated Multnomah County land until it and Gresham became contiguous. Stumptown, like some gigantic, hungry leucocyte, blobbed around its smaller neighbor and now completely encircles it.

Give how small Maywood Park is, you might think that it sets some record for being the smallest incorporated area in the U.S. But, it’s not. At 0.17 miles, Maywood Park isn’t even the smallest incorporated area in Oregon. Greenhorn, Oregon is, with an area of only 0.1 miles, however no one actually lives there. Several states also have tiny little teacup cities that exist for some reason.

Maywood Park is not a real city in any meaningful way. Kids there go to schools in the Parkrose District, and Maywood Park uses several Portland city services.

The enclave seems to maintain its independence mainly because of inertia. They incorporated for a specific reason, and have never gotten around to officially joining Portland. Which is… fine? Given that Portland is utterly devoted to a small circle of grass being an official city park, I suppose we can put up with Maywood Park calling themselves a city.

Drew asks: Why don't we cover 405?

And, while we’re talking about highways, let’s spend a little time with I-405, one of the ugliest pieces of infrastructure in the Rose City.

Portland’s 405 is a monstrosity. It cuts through the Pearl District, Downtown, and Goose Hollow, abruptly slicing through walkable urban areas, giving way to cars, noise, and pollution. I don’t know how many concerts I’ve been to at the Crystal Ballroom, but it’s always a bit of a comedown to get out of a show, filled with the energy and lightness that only live music can bring, and then run smack into a highway.

But what if, instead of having a filthy, noisy, highway cutting through the West Side, we buried it? What if 405 (or even other highways) were entombed within the Earth, leaving us surface-dwellers in peace? And, after burying the highway, what if we wrapped garlic around its neck and put a stake through its heart to make sure it never rose again? It’s a beautiful possibility.

This idea’s been floating around for a while. Former Portland Mayor Vera Katz wanted to cover both the 405 and I-5, and experts have looked into how much this would cost. According to the Willamette Week 2005 analysis by Nohad Toulan, the former dean emeritus of Portland State University’s College of Urban Affairs put the price tag between $3.5 billion and $5.8 billion.

That’s a lot, but it’s not an impossible amount of money. It’s also not the kind of cash that local governments have just lying around. Capping Portland highways would take some major political organization, but it’s hardly an unrealizable dream. Boston buried one of their highways, albeit with some major difficulties. We can probably do them one-better.

More immediately, I’d love to see MAX and Tri-Met extend out to Vancouver as a means for mitigating the day-to-day traffic in the city, but that’s another rant. Burying highways is all well and good, but it would be even better to make them less crowded, less in-demand, and less necessary.

Do you have a question about Portland? Send me an email and I’ll try to get to it in a future column.